From 1952 to 1981, South Africa’s apartheid government operated a training school for art teachers in the Bantu Education system — the school system for black South Africans.

Although primarily intended as a place to train teachers, the school, known as Ndaleni, offered black South Africans the largely unheard-of opportunity to learn art history and to train as artists. This opportunity came at a price: Upon completing the course, the students were to teach in a Bantu school for at least a year, entangling them with the apartheid state.

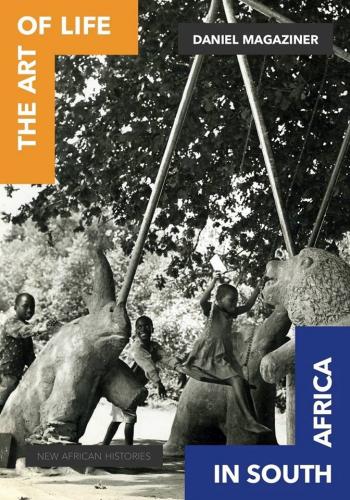

“The Art of Life in South Africa,” a new book by Yale historian Daniel Magaziner, tells the story of Ndaleni’s students and teachers, the art they created, and the compromises they made — providing insights into the complexities of life under apartheid.

Magaziner, an associate professor of history, spoke with YaleNews about the book. An edited version of the conversation follows:

How did you come upon the story of Ndaleni?

I had finished my first book, “The Law and the Prophets,” which was about the student movement in the 1970s in South Africa. The movement insisted that politics in South Africa was to be a matter of “being.” It called people to be engaged with their full selves, and it insisted that one of the manifestations of that was that you couldn’t make apolitical art. If art didn’t comment on the politics of the day, then it was irrelevant, and the worst thing to be was irrelevant.

This was familiar to me because in many ways it echoed the art historical literature about black South Africans, which tends to agree that the only way you could read black South African art was through the lens of apartheid and the struggle. This agreement felt historical to me, which is to say that I felt that there must be other ways of reading it.

I began to study the history of black artists and art in South Africa, but I had a difficult time finding documents and voices; I was treading water. Eventually I came upon a biography of an artist, which cited some letters he’d written to someone I’d never heard of, but they were letters, and I didn’t have many documents. I went to the archive where they were held and was shown an entire file cabinet of material concerning Ndaleni. It was the complete archive of the school from 1963 to 1981. Most people in South Africa have never heard of the school.

Read the full article at Yale News.