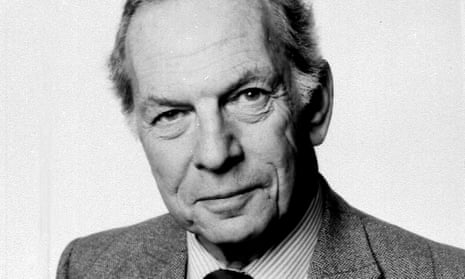

Michael Howard, who has died aged 97, was the most influential British military historian of his generation. He left a mark on public and professional debate in Britain and internationally. He also had a key part in building institutions: what is now the International Institute for Strategic Studies, based in London, which became the model for similar thinktanks around the world; what is now the Sir Michael Howard Centre for the Study of War at King’s College London; and the graduate studies programme in international relations at Oxford University.

He enjoyed a unique combination of beliefs, skills and, as he freely admitted, luck. The unifying theme of all his work was the placing of military history and strategic thought in the broadest social and political context.

In his view, armed force is an ineluctable element in international relations. He also knew how catastrophic official decision-making on war often is. The approach to international security that he advanced avoided the pitfalls of hawkishness and pacifism. His writing and lecturing was trenchant and accessible. He combined intellectual distinction with common sense. His views were respected even by those who took a different stance.

He was the epitome of respectability, even grandeur: a Guards officer, member of the Athenaeum, regius professor, author of official histories of the second world war, and recipient of honours including the Military Cross, a knighthood (1986), CH (2002) and OM (2005). Yet he also had a non-conformist streak, reflected in his support throughout the cold war years for tempering nuclear deterrence with moderation and for practical measures of arms control. Nonconformism also infused other aspects of his life.

The 21 years he spent at King’s began in 1947 with a lectureship in the history department, covering Europe from 1500 to 1914. It was on the strength of his first big book, The Coldstream Guards 1920–1946 (1951, co-authored with John Sparrow) – which he later played down as “my regimental war history” – that he was appointed in 1953 to a newly created lectureship in military studies at King’s. This appointment, enabling him to escape the history department, where he had not been happy, was made at a time when the world was still trying to digest the implications of the first tests of thermonuclear weapons by the US and USSR.

In the next 10 years, he embarked on a “voyage of discovery”. He had to acquire at least an acquaintance with various technologies, civil-military relations, defence decision-making and revolutionary war. His writing was sometimes stronger on generalisation than on detail. “I had to skim the surface of many disciplines without having the chance thoroughly to master any one.”

His first book contribution to policy debates, Disengagement in Europe, came in 1958, the year that the then Institute of Strategic Studies was founded. Its subject, possible force reductions in central Europe, was controversial: Michael’s voice was recognised as calm and wise.

At the same time he was deeply alarmed about the possibility of nuclear war. Over 40 years later he revealed to me that in 1958 he had obtained by unofficial channels two suicide pills, as a precautionary measure because of his concern about what to do in the event of a nuclear war. He said he had recently got rid of the pills, but kept the envelope in which they had come. He indicated that his worries had probably resulted from a combination of factors — the disputes over Berlin, and the “use them or lose them” nature of surface-based and liquid-fuelled missiles of that time; and that in the 1980s, at the time of controversies about nuclear missiles at Greenham Common and elsewhere, he was again very worried.

Military history remained at the centre of his work. His masterpiece, The Franco-Prussian War (1961), reflected his interest in the changing nature of war and the role of force in the process of German unification in the 1860s and 70s. He viewed France’s decision to go to war as catastrophic.

In writing this book, Michael had from 1958 engaged as a research assistant Mark James, whose help was acknowledged in the preface. From 1961 onwards, apart from two years when Mark was teaching in Ghana, they lived together. In 1964 they bought a house in the village of Eastbury, Berkshire – initially as a weekend and holiday retreat from London-based jobs, and later as a main home. There they pursued shared interests in music and gardening. At first the relationship had to be discreet and a distinction drawn between public and private.

In 1963 Michael was appointed professor of war studies at King’s, where his pre-eminent achievement was building up the department of war studies and recruiting to it an impressive and intellectually diverse group of scholars. It attracted graduate students from near and far.

He consolidated his reputation as a writer and broadcaster on military issues. In 1968, three days after the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia, he gave a talk on BBC Radio’s Third Programme showing cool judgment about an event that unnerved many. While recognising all the reasons why this was seen as a disaster that stirred deep emotions, he argued cogently that it actually reinforced the case for building up contacts with communist countries.

Later that year he moved to Oxford, as a fellow in higher defence studies, one of several posts established on the initiative of the Ministry of Defence. In 1977 he was elected Chichele professor of the history of war. Both positions were at All Souls College, from which he contributed to the growth of graduate studies in military subjects and international relations throughout the university.

Then in 1980 he became regius professor of modern history, an appointment in which the prime minister had the final say. Some commented that he got the job because Margaret Thatcher liked his views, but such muttering diminished greatly over time. As regius professor (and now at Oriel College) he had to devote himself mainly to the faculty of modern history, helping to steer through some overdue reforms to Oxford’s excessively anglocentric syllabus.

His record of publication in his 21 years at Oxford was formidable. Nine major books in that period included the volume in the UK Official History of the Second World War on Grand Strategy (1972), the authoritative translation of Carl von Clausewitz’s On War (with Peter Paret, 1976), a gem-like survey of War in European History (1976), and the deeply reflective War and the Liberal Conscience (1978). He also published an edited collection, Restraints on War (1979), that successfully explored the impact of the laws of war in recent history.

One major work done at Oxford was published only later. He wrote Strategic Deception (1990), a volume of the official history of British Intelligence in the second world war. The research into it, on which he embarked in the mid-70s, required him to undergo positive vetting procedures. (Grand Strategy had called for more modest vetting.)

A relatively low-grade vetting officer went through the motions of saying he assumed there was no question of Howard being a communist or homosexual. The answer came: “I am a homosexual: let’s get that out of the way.”

In later questioning, the Security Service came up with some titbits of information demonstrating impressive assiduity (a note to Guy Burgess, a library request by Mark for a map of the Danish coast), but Michael and Mark passed the test – remarkably, as at that time homosexuality was generally viewed as an automatic bar to PV clearance. After Strategic Deception was completed, its publication was held up for 10 years by Thatcher, worried about revealing how the intelligence services operated. The book appeared only in the last year of her premiership.

In 1989, a year before he was due to retire from Oxford, Michael resigned from the regius chair to go to the US as professor of military and naval history at Yale University. This post enabled him to extend his active teaching career to the age of 70. At Yale, Mark was listed as a spouse, and Michael produced The Lessons of History (1991) and a co-edited volume on The Laws of War (1994).

Born in London, Michael was the youngest of the three sons of Geoffrey Howard, chairman of Howard and Sons, a pharmaceutical firm, and his wife, Edith (nee Edinger), from a German Jewish family. The family lived in South Kensington and gradually spent more time in Ashmore, Dorset.

Among the Howards there were strong anti-war and humanitarian traditions: Geoffrey and his sons were Anglican, while Michael’s aunt Elizabeth Fox Howard, a Quaker, helped objectors in 1914-18, and was later to be active in assisting victims of the Nazis.

At Abinger Hill, a prep school in Surrey run on the same progressive principles as Bryanston, Michael enjoyed English and history. He then went to Wellington college, Berkshire, where he benefited from outstanding teaching.

After the second world war broke out in 1939, his call-up was deferred when he won a scholarship to Christ Church, Oxford, to read modern history. He started his studies in January 1941 and got a first in the “shortened” honours degree the subsequent year. He then followed many of his Oxford friends into the Coldstream Guards, becoming a second lieutenant in December 1942.

He seldom spoke of his experiences of war, or of how he came to be nominated for the MC, which is awarded for acts of exceptional bravery. Posted first to North Africa, and now with the rank of lieutenant, in September 1943 he joined his unit on the beaches of Salerno in the first major allied assault on Axis-held Europe.

On 22 September, facing close-range German machine-gun and grenade fire, he led a platoon to capture a small hill, for which he was awarded an MC. Much later, asked about these events, he said that it was only because he was so young (still only 20), and so ignorant, that he could perform such an act.

At the end of 1946, having resumed his studies, but finding it hard to focus on academic work, he got a disappointing second class degree. This was his salvation. Instead of settling in to the life of an Oxford don, he had to earn his living in the outside world. Unlike his two older brothers, and sensing that he was more intellectually inclined, he chose not to go into the family firm (which, in the event, was swallowed up in the 1950s), but went instead to King’s.

After his “retirement” in 1993, Michael continued to be intellectually active. He produced a short book, The Invention of Peace (2000), full of pithy scepticism about propositions that history had ended.

He publicly criticised the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. In 2003, as a visiting professor in Washington DC, he denounced the Iraq war as “a bad idea whose time has come”. Then came his memoir Captain Professor (2006), a frank account of his full, productive and fortunate life.

In his 80s Michael’s life gradually became a real retirement, firmly anchored at Eastbury, where he enjoyed the large garden. On the first day on which it was possible to do so – 21 December 2005 – Michael and Mark entered into a civil partnership, rectifying, as Michael said, an anomaly of over 40 years.

Their visitors at Eastbury found Michael, despite partial deafness, as interested in events and shrewd in his judgments as he had always been.

Mark survives him.

Michael Eliot Howard, military historian, born 29 November 1922; died 30 November 2019

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion